Uganda’s military: What do we know about HIV programming?

Gloria Seruwagi

- March 8, 2021

Growing up I was always fascinated by soldiers. Mostly strong, controlled with very few words but heavy action and a whole protective vibe around them, they always seemed quite a mystery. Growing up in a family with three soldiers you could always tell they were different but not entirely sure how – their worlds were very private. Even when I studied two full years of my primary at an army school, living with one of my soldier uncles and fully immersed in the “barracks and army boarding school” life, I still left without ever fully understanding them – neither my uncle nor the barracks community. So I grew up with “part-knowledge, part-curiosity” about this group of people and their communities, the military.

In 2019 three colleagues and I started on a journey to work on a project we’ve called SUPREME, an acronym for Supporting Research and Evidence-based implementation through Mentorship, learning and dissemination. The SUPREME Project aims to support the sharing of program implementation experiences on HIV Prevention, Care and Treatment (PCT) in military settings. The key word being HIV in military settings. A very important and exciting project, no doubt, but one that caused me to wonder – before we even get to HIV/AIDS, how much do we really know about life in the military? About soldiers? What prejudices or attitudes do have towards them? What assumptions have we made – that’s if we have any at all?

The military remains a very guarded group and inaccessible space to civilians and anyone outside. They operate by their own [different] rules. They are matching to a different drummer. They look strong and ready for battle at all times. They pay huge sacrifices and take on bold actions that may sometimes never be known or appreciated. But yet they continue soldering on. So, how does HIV come into the picture? Soldiers usually come off as very strong people, so it is not a common picture for the ordinary person to imagine them frail or sick, ravaged by disease, affected by the infamous virus. Military health facilities are some of the very best Uganda has got – in terms of cleanliness, infection control, stock and service delivery. Everything seems to be in place; but this great service delivery in military health facilities and the resulting health outcomes remain more like a “black box” where little is known by the outside world. Yet a lot of great things are happening there; and our men in uniform actually like to connect with people around them. Did you know, for example, that communities around military health facilities say they prefer services there? Did you know that these health facilities are open to serving communities, including civilians who are not military family members? What about the fact that there are some great programs for Orphans and Vulnerable Children (OVC) and youth being implemented in these military settings?

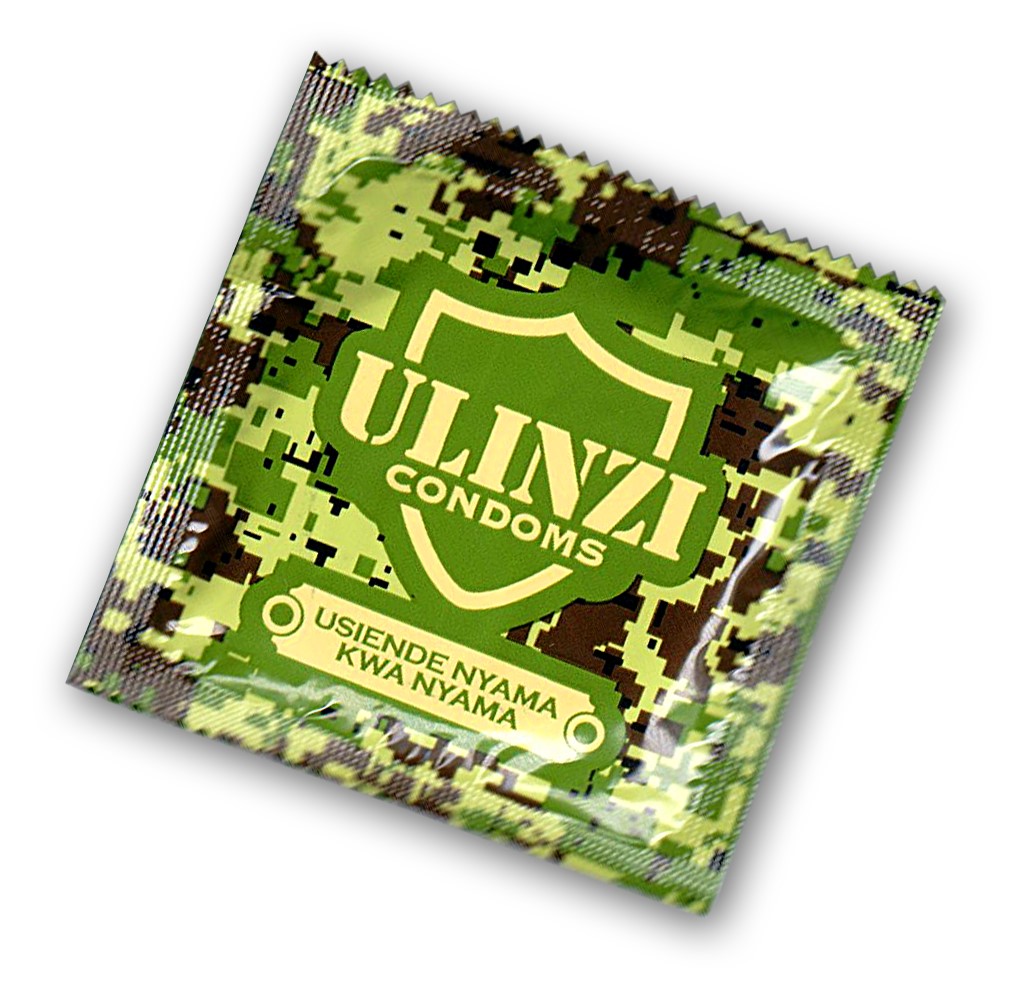

So, it’s wonderful that the URC’s Department of Defense HIV/AIDS Prevention Programme (DHAPP), funded by PEPFAR and implemented in partnership with Uganda Peoples Defense Forces (UPDF), has embarked on this journey of sharing implementation experiences of implementing HIV Prevention, Care and Treatment (PCT) in military settings across the whole of Uganda. The program is being implemented in 28 military health facilities in all regions of Uganda and other accredited ART Centres. And the SUPREME project is just one of these avenues for dissemination of implementation experiences. For example, Dr. Abdul Nyanzi and a number of colleagues have recently published a paper on how DHAPP adapted the WHO’s Models for Optimizing Volume and Efficiencies (MOVE) to accelerate access to voluntary male medical circumcision (VMMC) for HIV prevention in Uganda’s military; which led to an exponential increase in VMMC coverage from 13% to over 120% in Q4 in a four months period. This is against the backdrop that men in uniform, including the military, are listed among the “Priority Populations” (PP) in the HIV prevention fight. The nature of soldiers’ life is highly mobile and risky; so they need to be targeted, protected and supported. For example, sometime back a bespoke camouflage condom called Ulinzi [protection] was launched – exclusively branded for soldiers to scaleup HIV protection.

This is just one of the many initiatives happening in the military; but how much does the outside world know on its uptake, effect or extent of its contribution?

So – back to Nyanzi et al’s paper on a 120% increase in VMMC coverage: to have those high numbers access VMMC’s partial protection is no mean feat, it is an achievement that should be celebrated. More importantly, we should be asking the question – how did it happen? How is it done in the military context? What explains this success? How really was the WHO model operationalized (because its actual implementation varies in different settings across the world) and what local adaptations were made? What can non-military settings learn? Dr Nyanzi together with co-authors present and explain the URC-DHAPP adapted intervention package comprising of: a) leveraging the military’s “Command-Driven” Approach, not just for battle but for HIV work; b) Mobile Theatres in hard-to-reach-places; c) Quality Assurance; d) Data Strengthening and Reflection. With this multi-pronged and robust model tailored to soldiers’ contexts perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that URC-DHAPP registered the VMMC success it did. And here’s to more HIV prevention!

We’ll be hearing more from military men and women, some in dual roles as both soldiers but also diligently and excellently practicing their professions. We shall be learning lessons from the military fraternity but also other technical staff implementing programs in these unique military settings. Another published manuscript, a Case Report, describes how they managed a tetanus Adverse Event (AE) after VMMC in a Pre-circumcision Tetanus Immunized Male. We shall learn more about the Command-Driven Approach (CDA) or exactly how the Differentiated Service Delivery Model (DSDM) is being implemented in the military. We shall hear about the innovative healthcare practices and prevention strategies being applied, as we race towards elimination of HIV and reaching the 95-95-95 targets by 2030.

About the Interview

Gloria is behavioural scientist with interest in health systems, community health, DVM (Disadvantaged, Vulnerable and Marginalized) populations. She is Team Lead for the SUPREME Project.